![]() If we would make a poll about the most fundamental question of electrostatics, the field of a point charge is very likely the winner. You may already know the answer but are you able to derive it directly from Maxwell's equations?

If we would make a poll about the most fundamental question of electrostatics, the field of a point charge is very likely the winner. You may already know the answer but are you able to derive it directly from Maxwell's equations?

Problem Statement

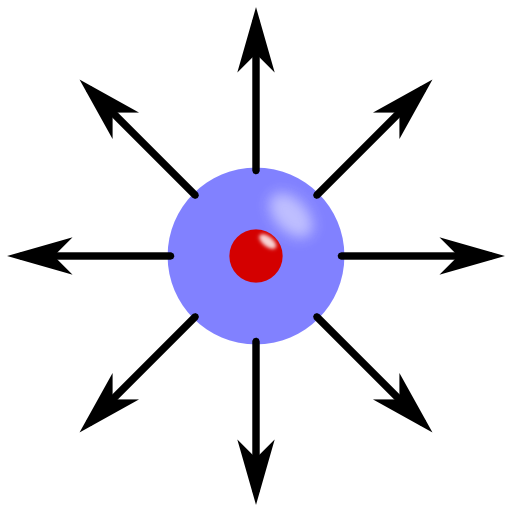

Consider a point charge \(q\) in vacuum, e.g. an electron or proton. What is the resulting electric field \(\mathbf{E} \left( \mathbf{r}\right) \)?

Can you relate Coulomb's law to this force?

Background: From Forces to Fields

The electric field of a point charge is the most fundamental concept in electromagnetism. Historically, the force between two charged objects was found to scale with the product of the object's charges their inverse squared distance. This force is now known as Coulomb's law and was found in the second half of the 18th century.

The field concept is however a little different. Given a charge, one can calculate the force acting on a test object with unit charge. This force, in appropriate units, is then called the electric field. You can use the results from this problem to find the electric field of an arbitrary charge distribution using the principle of superposition see the electric field of two point charges.

Hints

Which one of Maxwell's equations relates the electric field to charges?

What is the corresponding integral form?

Now, let's jump into the mathematical solution of the electric field for a point charge. It will not be complicated but very insightful!

First of all we will derive the field of a point charge from Gauss's law when the charge is centered at the origin. Then we can generalize our result to an arbitrary position. Finally, let us relate the field to Coulomb's force.

Calculating the Field from First Principles

Without loss of generality we can place the point charge at the origin \(\mathbf{r}=0\). The only Maxwell equation we have to use is Gauss's law

\[ \begin{eqnarray}\nabla\cdot\mathbf{E}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)&=&\frac{\rho\left(\mathbf{r}\right)}{\epsilon_{0}} \end{eqnarray}\]

relating the charge density \(\rho\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\) to the electric field \(\mathbf{E}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\). We obtain that after an integration over a volume \(V\) containing the charge \(q\) we are left with

\[ \begin{eqnarray} \int_{V}\nabla\cdot\mathbf{E}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)dV = \frac{1}{\epsilon_{0}}\int_{V}\rho\left(\mathbf{r}\right)dV=\frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}\ .

\end{eqnarray}\]

At this point we can use the divergence theorem

\[\int_{V}\nabla\cdot\mathbf{F}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)dV\] and

\[=\oint_{\partial V}\mathbf{F}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\cdot\mathbf{n}dS\]

with the normal vector of the surface \(\mathbf{n}\). This transforms Gauss' law into a surface integral:

\[ \begin{eqnarray} \int_{S}\mathbf{E}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\cdot\mathbf{n}dS&=&\int_{S}\mathbf{E}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\cdot\mathbf{e}_{r}r^{2}\sin\left(\theta\right)d\theta d\varphi\\&=&4\pi r^{2}E_{r}\left(r,\theta,\varphi\right)\\&=&\frac{q}{\epsilon_{0}}\ .\end{eqnarray}\]

Here, \(E_r\) and \(\mathbf{e}_r\) indicate the radial component of the electric field an the unit vector in radial direction, respectively.

The charge is situated in the center of the coordinate system. So, there cannot be any other electric field component than the radial one. We find that

\[ \begin{eqnarray} \mathbf{E}\left(r,\theta,\varphi\right)&=&\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{r^{2}}\mathbf{e}_{r}\end{eqnarray}\ .\]

A Charge in an Arbitrary Position

If we want to know the field of a point charge situated at an arbitrary position \( \mathbf{r}_{q} \), the use of a spherical coordinate system is possible but not very clever. We have to transform the field into a cartesian form. The radial unit vector is given by \(\mathbf{e}_{r}=\mathbf{r}/\left|\mathbf{r}\right|\), so we find the electric field as \[\mathbf{E}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)=\frac{q}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{\mathbf{r}}{\left|\mathbf{r}\right|^{3}}\ .\]Now we have to consider the new position of the charge. This can be realized by a shift using \(\mathbf{r}_{q}\):\[ \mathbf{E}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)=\frac{q}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{\mathbf{r}-\mathbf{r}_{q}}{\left|\mathbf{r}-\mathbf{r}_{q}\right|^{3}}\ .\]

Now that we know the electric field for one point charge in a rather general form, we can calculate the resulting field for general charge configurations. This can be done using the principle of superposition. One example is the electric field of two point charges.

The Coulomb Force

From a general point of view, a charge can be seen as a coupling constant of an object to a given field. The electrostatic force acting on that object \(q^\prime\) is then simply given by

\[\mathbf{F}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)=q^{\prime}\mathbf{E}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\ .\]

For the field of a point charge which we have just calculated, we find that the force is just Coulomb's law.

Congratulations, you have just found the solution to the most basic charge configuration!

Way to go, there are a lot of topics to cover in the electrodynamics course!