![]() In an attempt to explain the electron spin in a classical model, one can assume that it is just a rotating charged particle causing a magnetic moment. However, such an approach results in contradictions which renders a classical explanation of the intrinsic magnetic moment of an electron obsolete.

In an attempt to explain the electron spin in a classical model, one can assume that it is just a rotating charged particle causing a magnetic moment. However, such an approach results in contradictions which renders a classical explanation of the intrinsic magnetic moment of an electron obsolete.

Problem Statement

One way to find contradictions in such a classical argumentation is to find a lower estimation for the angular velocity at which an electron would have to spin to cause its magnetic moment:

One way to find contradictions in such a classical argumentation is to find a lower estimation for the angular velocity at which an electron would have to spin to cause its magnetic moment:

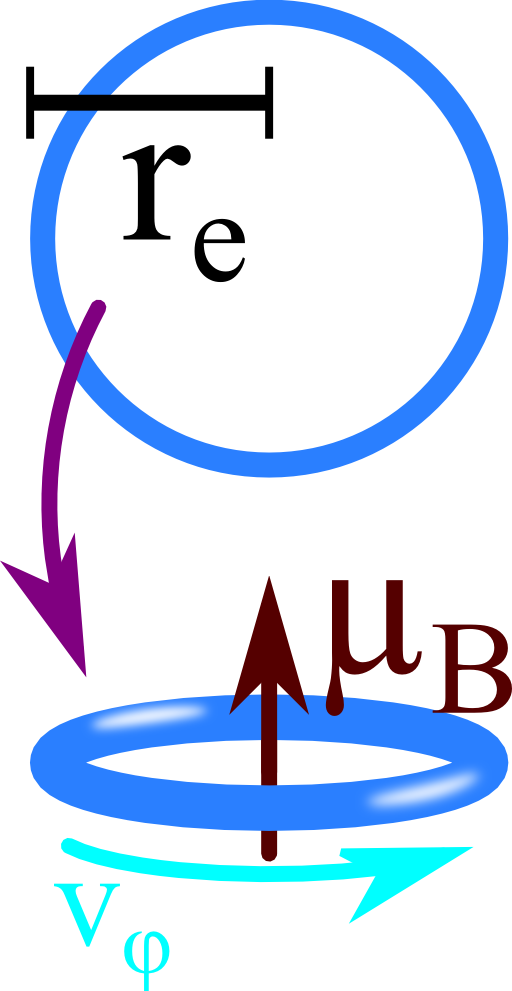

Find a classical electron radius re: Regard the electron made of a thin charged shell with radius re. What is the electrostatic energy of such a configuration?

Determine re by equating this energy with the rest energy of the electron, \(E_0=m_{e}c^{2}\).

Calculate a lower limit for the electron's classical angular velocity \(v_{\varphi}\): To keep things as simple as possible, assume the electron now as a rotating charged loop with radius re.

Compare the resulting magnetic moment to the (approximate) magnetic moment of the electron, the Bohr magneton

\[\mu_{B} = \frac{e\hbar}{2m_{e}c}\ .\]

Express your result in terms of the fine-structure-constant

\[\alpha = \frac{e^{2}}{4\pi\epsilon_{0} \hbar c} \approx \frac{1}{137}\ .\]

Physically, does your result for \(v_{\varphi}\) make sense?

Hints

Remember that the electrostatic energy of a charge configuration \(\rho\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\) with potential \(\phi\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\) is given by

\[E = \frac{1}{2}\int\rho\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\phi\left(\mathbf{r}\right)dV\ .\]

Can you figure out the current \(I\) for a loop when the total charge per period \(T=2\pi/\omega\) is given by one elementary charge \(e\)?

Let's move on and answer the questions!

The Classical Electron Radius

If we assemble some charges to a shell of total charge \(e\), the energy needed to achieve this is the electrostatic energy of the shell,

\[E = e\frac{1}{2}\phi_{e}\left(r_{e}\right)=\frac{1}{8\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{e^{2}}{r_{e}}\ .\]

Here, \(\phi\left(r\right)\) is just the potential of a point charge for which we know that it has to be the usual \(1/r\)-solution outside of the shell following Gauss's law. Hence it must be the potential acting on every single charge element inside the shell and we get the above expression. Considering the problem for example with respect to a homogeneously charged sphere would result in some minor change of \(E\).

However we will see shortly that anything that doesn't hugely change our results will have no impact on our end result so we can keep things as simple as possible.

Now this energy with the energy of the rest energy of an electron, we get

\[\begin{eqnarray*}m_{e}c^{2}&=&\frac{1}{8\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{e^{2}}{r_{e}}\ ,\\r_{e}&=&\frac{1}{m_{e}c^{2}}\frac{e^{2}}{8\pi\epsilon_{0}}\approx1.4\times10^{-15}\,\text{m .}\end{eqnarray*}\]

Note that this result is half of the usual result referred to as classical electron radius. But this should not bother us since by this prediction the electron would still be bigger than an approximately two thousand times heavier proton with \(r_{p}\approx0.8\times10^{-15}\,\text{m}\), see Pohl et al., Nature 466 (2010).

So it might be save to assume our re as an upper bound. We will see soon that a smaller radius would correspond to even higher spin rates, so there is again no problem in our approximation.

An Incredible Angular Velocity

For the second part of the problem, the electron is represented by a rotating loop charge with radius re. Since the current equals one \(e\) per period \(T=2\pi/\omega\), we find

\[\begin{eqnarray*}\mathbf{m}&=&\frac{1}{2}I\int\mathbf{r}\times d\mathbf{r}\ ,\\m_{z}&=&\frac{1}{2}\frac{\omega e}{2\pi}\int r_{e}^{2}d\varphi=\frac{1}{2}e\omega r_{e}^{2}\end{eqnarray*}\]

using \(\mathbf{r}_{\mathrm{loop}}=r_{e}\mathbf{e}_{\rho}\) and \(d\mathbf{r}=r_{e}\mathbf{e}_{\varphi}d\varphi\).

Now we can replace the angular frequency \(\omega\) by the angular velocity, \(v_{\varphi}=r_{e}\omega\), and equate the magnetic momentum with the Bohr magneton:

\[\begin{eqnarray*}\mu_{B}=\frac{e\hbar}{2m_{e}}&=&\frac{1}{2}er_{e}v_{\varphi}\ ,\ \mathrm{so}\\v_{\varphi}&=&\frac{e\hbar}{2m_{e}}\frac{2}{er_{e}}=\frac{\hbar}{m_{e}}m_{e}c^{2}\frac{8\pi\epsilon_{0}}{e^{2}}\\&=&2\frac{4\pi\epsilon_{0}\hbar c}{e^{2}}c=2\frac{c}{\alpha}\gg c\ .\end{eqnarray*}\]

We find that in our classical model the angular velocity would have to be in the order of 200...300 times the speed of light! Again, this is still a lower estimation. The most severe approximation was indeed made in our \(r_{e}\).

Realistically, the electron is much smaller if it does even useful to assign it some spatial expansion. Assuming such a scenario we would even find a still much larger angular velocity. Hence, a classical explanation of the spin of an electron in terms of a rotation simply doesn't make sense, it is an intrinsic property!

Background: The Magnetic Moment of the Electron

The electron is characterized by three different numbers: charge, mass, and spin. Since the famous oil-drop-experiment by Fletcher 1909 under the supervision of Millikan one knew that the electron has both fixed charge and mass. The latter one follows because of known results from charge to mass ratio experiments performed by Thomson at the end of the 19th century. What about the spin and the magnetic moment of the electron? Here, the Stern-Gerlach experiment in 1922 showed that quantum particles have an intrinsic quantized magnetic moment. All these findings had a deep impact on fundamental physics and were extremely important for the formulations of relativistic quantum mechanics (Dirac) and quantum electrodynamics (Tomonaga, Schwinger, Feynman).

So we know that the intrinsic magnetic moment has to be quantized. Indeed, quantum mechanics tells us that the total magnetic moment has to be related to the spin \(\mathbf{s}\) of an electron and of course to its actual motion e.g. orbiting a hydrogen atom with angular momentum \(\mathbf{L}=\mathbf{r}\times\mathbf{p}\).

Starting from the spin-free Hamilton of an electron in a (electro)magnetic field with vector potential \(\mathbf{A}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\),

\[\begin{eqnarray*}H&=&\frac{1}{2m}\left(\mathbf{p}-e\mathbf{A}\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\right)^{2}+\phi\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\\&\approx&\frac{\mathbf{p}^{2}}{2m}-\mu_{B}\mathbf{B}\cdot\frac{\mathbf{L}}{\hbar}+\phi\left(\mathbf{r}\right)\ ,\end{eqnarray*}\]

we find that the magnetic moment should be something like \(\mathbf{m}_{L}=\mu_{B}\mathbf{L}/\hbar\). Now, we may simply replace the electron angular momentum (operator) \(\mathbf{L}\) with the intrinsic angular momentum (spin) \(\mathbf{s}\). Such an approach, however, is not justified since angular momentum and spin behave differently. This difference is known as the Landé-factor \(g\),

\[\mathbf{m}_{s}=\mu_{B}g\frac{\mathbf{s}}{\hbar}\ .\]

The Landé-factor can be calculated extremely precise within quantum electrodynamics as \(g\approx-2.002319\dots\). The difference to \(-2\) comes from the interaction of the electron with its surrounding vacuum. So the measurement of \(g\) gives a lot of insight into the applicability of quantum electrodynamics and is of great fundamental interest. If you are interested in how such highly nontrivial measurements can be done and how their results impact physics, you may want to have a look at the elaborated report “Cavity Control of a Single-Electron Quantum Cyclotron: Measuring the Electron Magnetic Moment” by Hanneke et al., Physical Review A 83 (2011) (or the more concise Physical Review Letter 100 (2008) by the same authors, arXiv, PDF).

Journal Page | arXiv | PDF